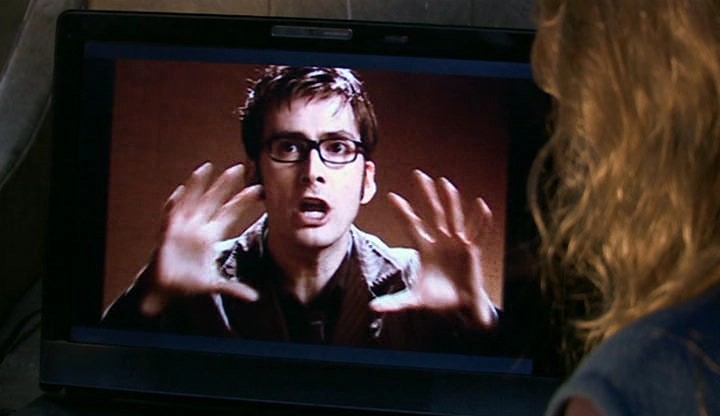

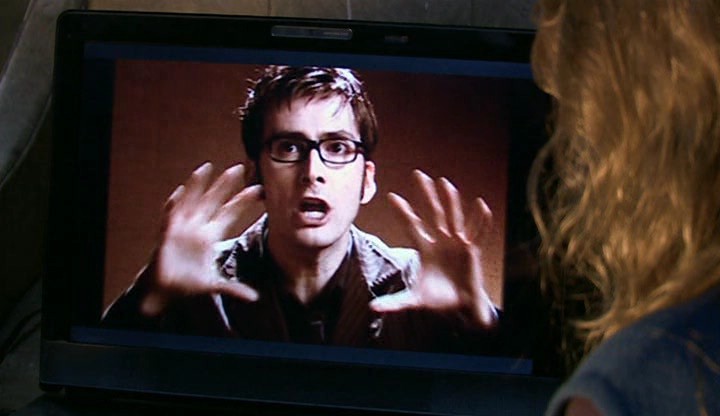

A lot of his stories are told out of sequence, involving flashbacks and different perspectives on the same events. In Doctor Who, time-travel means that not only can the story be told out of sequence, but the actual story can happen out of sequence. Moffat’s “wibbly wobbly timey wimey” storytelling has become one of his trademarks.

In the Question and Answer session, I asked Moffat if there was any particular reason that he likes this style of storytelling. His answer was that firstly it was just because he found it fun, but secondly, he said “Because – and here’s a spoiler for you! – there is no God” and went on to say that there’s no one “God’s-eye-view” of reality that’s definitive. Without even trying to ask a theological question, I got a theological answer!

But since the God of the Bible reveals him as trinity, as Father, Son and Holy Spirit in loving unity: you might almost say that there isn’t one “God’s eye view”, but three! If I wanted to sound pretentious (pretentious? moi?), I might call the Christian view “bounded multiperspectivalism”. But since I want people to understand me (and not just Swithun), I’ll say that the Christian view of reality is one where there are multiple perspectives, but within limits. There is diversity in God, since there are three distinct persons of the Godhead, and this means that there isn’t just one right way of looking at reality. But there is also unity in God, since Father, Son and Holy Spirit are one in love and substance with each other, and so there is a unity to reality, and so there are limits on what is true and false.

The Bible itself has the story of Jesus from four different authors with four different perspectives, in the four Gospels. For example, Matthew focuses on how Jesus fulfils the Jewish scriptures; Mark emphasises Jesus’ actions; Luke sets out to give an orderly, carefully investigated account (closest to our idea of historical writing); while John focuses on Jesus’ private teachings and sayings. Each gives a slightly different take on the Good News, and together they give a more complete and rounded understanding of Jesus’ life and mission in a way that is greater than the sum of the whole.

The Gospels aren’t necessarily told in strict chronological order, either. Matthew arranges his material thematically, around five main discourses, which some have suggested is intended to reflect the fivefold structure of the Pentateuch, for example, and if you compare the Gospels, you get the same stories in different places . This doesn’t make the Gospels wrong or unreliable – modern documentary makers will typically structure their material and put it in an order that best tells the story and puts across the ideas and themes they want to communicate. The use of carefully organised structure and of literary technique does not, in itself, make something historically inaccurate.

Simon Peter said to them : “Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life.” Jesus said : “Look, I will guide her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit like You males. For every female who will make herself male will enter the Kingdom of Heaven.”

For some reason, this is known as the “feminist Gospel”! While John’s Gospel contains dualistic language such as a lot of imagery concerning darkness and light which is superficially similar to the “Gospel” of Thomas, they are in fact very different. John’s writings concerns a moral dualism between the world in rebellion against God, and the Word from God who is not of the world, while out the hope of physical resurrection – the material can be redeemed.

By contrast, the Gospel of Thomas portrays a material dualism in which we need to escape an evil material existence for a pure and disembodied spiritual existence. But dualism of this sort leads to the suppression of difference and of physicality, as the closing lines of the Gospel of Thomas quoted above illustrates. This was seen in an extreme form in the medieval heresy of Catharism, which saw the physical world, and especially women, and especially sex, as inherently evil. The Church has sometimes been unfortunately influenced by such thinking, but trinitarianism allows for the celebration of diversity and difference as basically good, while balancing them with unity.

All this goes to show the wide-ranging impact of our theological beliefs. If you believe in the Trinitarian God of the Bible, or in a dualistic God of Gnosticism, or in no God at all, it will affect everything you do on some level – from how you treat women through to how you write television science fiction!